Did Harvard Professors Really Endorse Political Violence? The Truth Behind a 2018 Panel

Separating fact from rumor in the story of Harvard’s 2018 conference

In recent years, claims have circulated across certain corners of the internet suggesting that a group of Harvard faculty members once expressed support for potential left-wing political violence during a panel discussion in 2018. The allegation has been repeated in partisan blogs, comment sections, and in social media threads where accusations of elite institutions supposedly harboring radical or extremist tendencies often gain traction. Yet, when one looks closely at the available evidence, a different and far more complicated picture emerges, one that highlights the gap between academic discourse, political rumor, and the ways in which selective interpretation can turn an abstract scholarly debate into a sensationalized accusation.

Harvard University, long considered one of the most influential academic institutions in the world, has often found itself at the center of cultural and political battles. With faculty overwhelmingly self-identified as liberal or left-leaning, the university has become an easy target for critics who portray its classrooms and lecture halls as incubators for progressive ideology. A survey of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences conducted by the Harvard Crimson in 2018 showed that more than three-quarters of respondents described themselves as liberal or very liberal, while only a small minority claimed conservative affiliations. That survey has often been cited as evidence that Harvard’s academic environment is politically skewed. However, political orientation alone does not equate to endorsement of violence, and yet the claim that a panel of Harvard professors openly supported left-wing violence in 2018 has persisted in certain circles despite a lack of verifiable documentation.

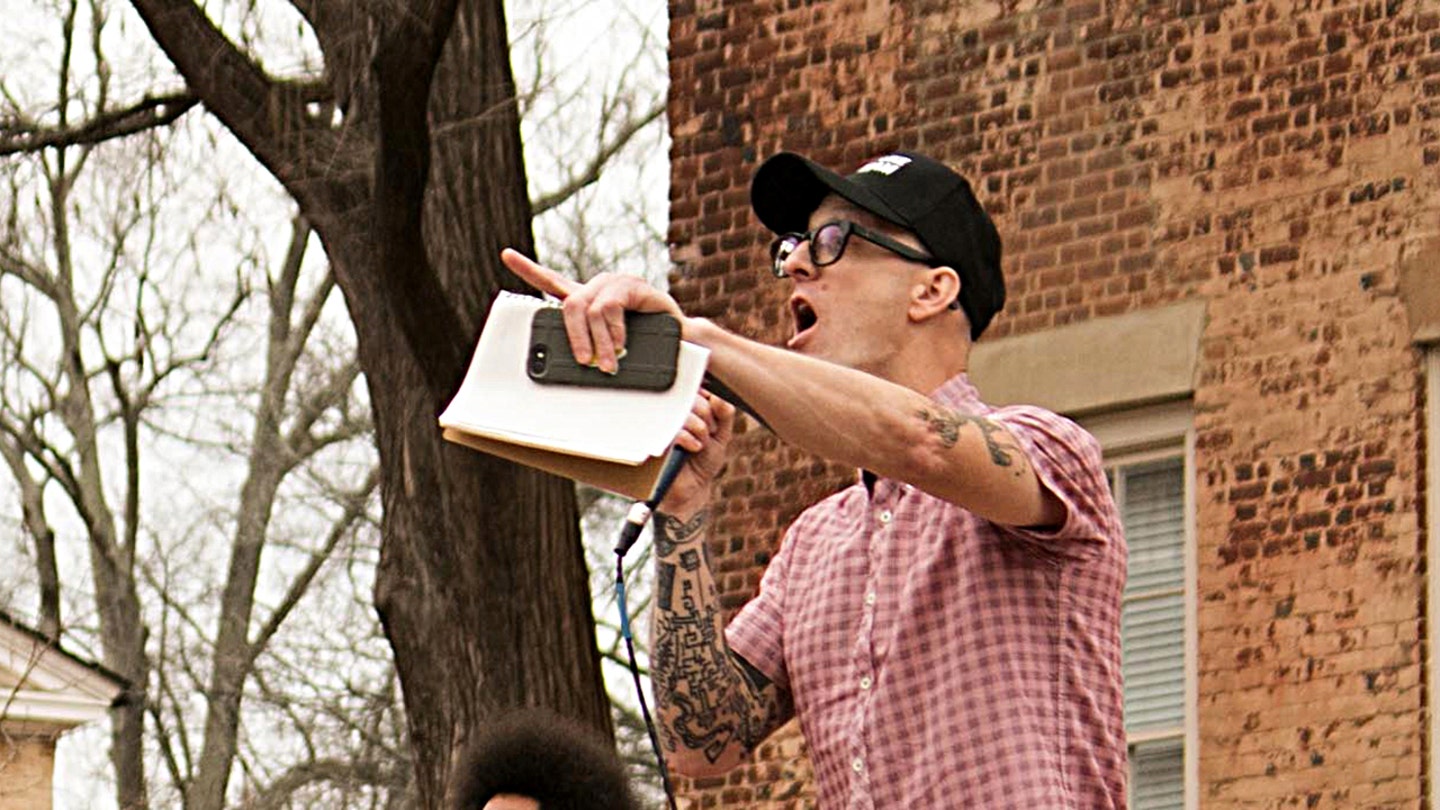

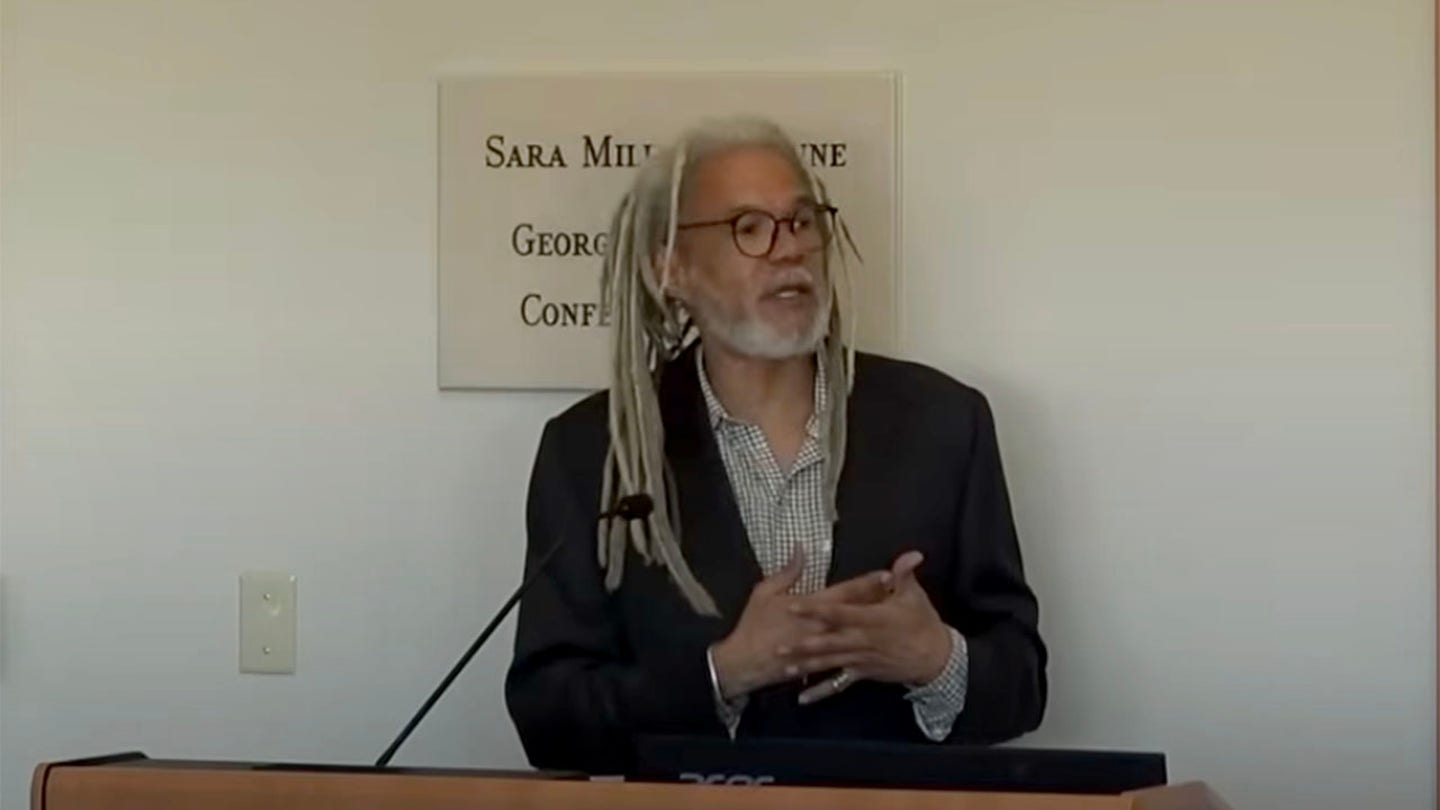

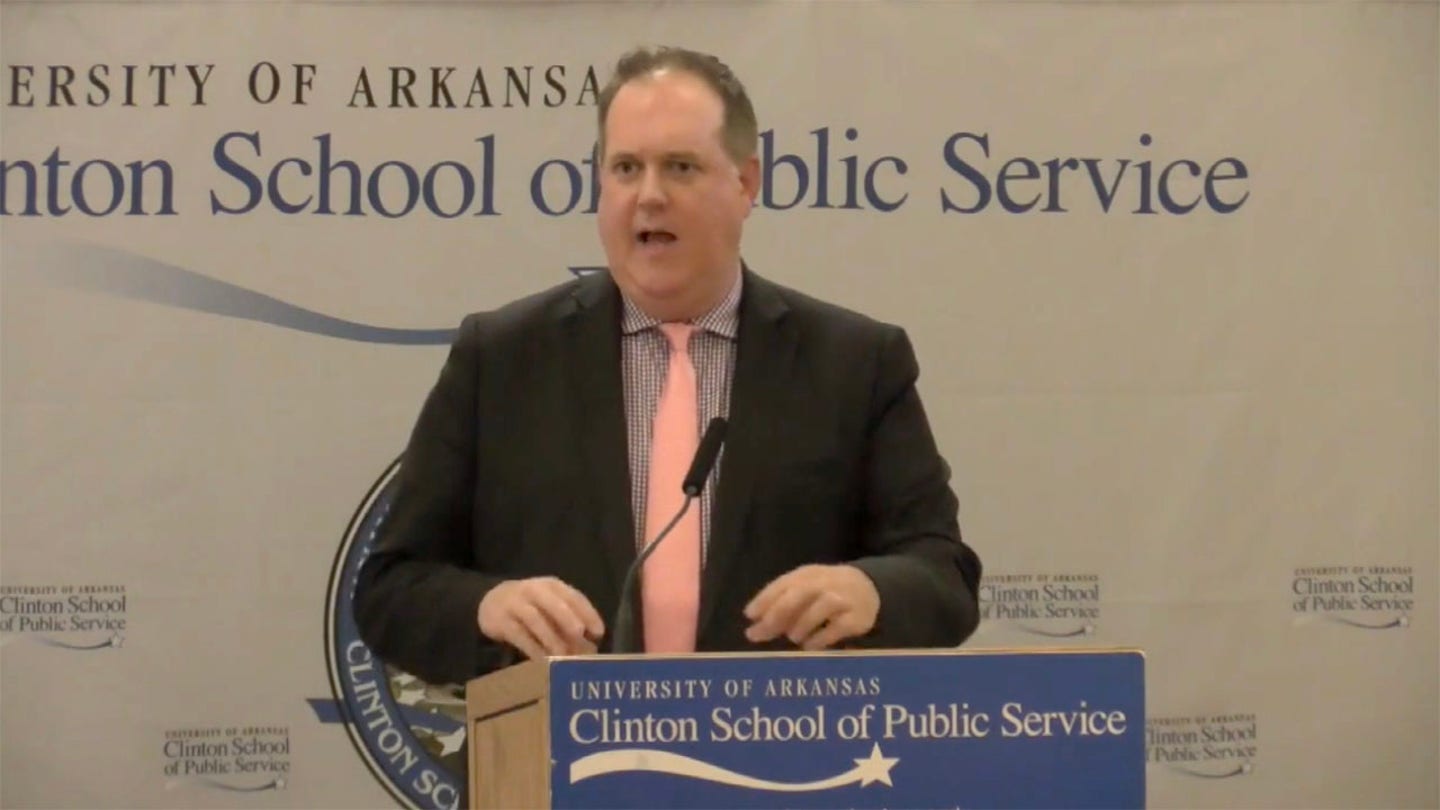

The roots of the allegation appear to stem from confusion surrounding an academic conference hosted at Harvard in 2018, known as the Harvard Experimental Political Science Conference. The event, like many scholarly gatherings, featured panels on subjects ranging from voter behavior to protest dynamics. According to the program published on the official Harvard site, one session included research presentations examining the framing of violent versus nonviolent protest in political communication. Scholars were not advocating for violence but analyzing how voters perceive violence in protest movements, how the media reports on it, and what effects those perceptions might have on democratic institutions. Such topics are standard fare in political science research, where violence is studied as an empirical phenomenon, not a normative prescription. But in a climate of polarized debate, a snippet from an academic discussion can easily be reframed in partisan rhetoric to suggest something far more provocative than was ever intended.

Part of the problem lies in how discussions of political violence are often received outside academic contexts. Political scientists regularly analyze events such as riots, armed uprisings, or state repression, asking questions about causes, consequences, and the effectiveness of violent versus nonviolent tactics. To the untrained ear, a scholar explaining that violent protests sometimes gain media attention more quickly than peaceful demonstrations might sound as if they are endorsing violence rather than describing a factual observation. Similarly, when researchers argue that governments sometimes only respond to protest movements once they escalate beyond peaceful means, those remarks can be misinterpreted as justifications rather than explanations. It is this gap between analytical language and public perception that may have allowed rumors about the 2018 Harvard panel to take on a life of their own.

At the same time, the allegation cannot be fully separated from the broader political discourse in the United States after 2016, when questions of protest, violence, and polarization dominated national headlines. From the protests in Charlottesville in 2017 to debates about Antifa and clashes between far-right and far-left activists, the atmosphere was already charged. Universities, as places where such issues were dissected and theorized, became symbolic battlegrounds themselves. Harvard, perhaps more than any other, was caught in the crosshairs of culture war narratives that cast higher education as aligned with radical leftist causes. Thus, when a handful of academic discussions about protest and violence surfaced in 2018, it became easy for critics to frame them as endorsements rather than analyses.

Efforts to locate direct evidence of Harvard faculty explicitly supporting left-wing violence in 2018 have consistently come up empty. No reputable outlet—whether the New York Times, Washington Post, Associated Press, or even Harvard’s own student paper, the Crimson—reported such remarks. What does exist are blog posts, op-eds, and social media threads from ideological platforms claiming that the conference or certain panels revealed dangerous sympathies. Yet, without transcripts, recordings, or credible witnesses, these claims remain unsubstantiated. In contrast, the available conference program and participant lists show panels devoted to experimental methods in political science, not political advocacy.

This episode illustrates how rumors can gain momentum when they fit into preexisting narratives. For critics of elite institutions, the idea that Harvard professors openly endorsed violence is a story too convenient to dismiss. It validates suspicions about academia’s radicalism and provides a powerful rhetorical weapon in debates over higher education. For supporters of Harvard and defenders of academic freedom, the allegation is an example of distortion, a warning about how easily scholarship can be twisted for political ends. The truth likely lies in the mundane reality that a group of academics discussed their research on protest, some of which touched on the role of violence, and that discussion was misunderstood or deliberately reframed.

What makes the persistence of this claim noteworthy is the broader question it raises about the relationship between universities and public trust. Across the United States, surveys have shown declining confidence in higher education, with partisan divides sharpening perceptions. Conservatives increasingly view universities as hostile environments, while liberals often see them as bulwarks against populist or authoritarian currents. In such a climate, even a technical panel on experimental political science can be weaponized to support a narrative of elitist corruption or radical indoctrination. The Harvard rumor, whether believed or debunked, thus becomes less about what was actually said in 2018 and more about what people want to believe about the institution itself.

Harvard has not issued any official statement specifically addressing the allegation about faculty support for violence at a 2018 panel, perhaps because from the university’s perspective the claim is baseless and does not warrant engagement. However, the university has repeatedly emphasized its commitment to academic freedom, the rigorous exchange of ideas, and the principle that scholarly inquiry does not equate to political advocacy. In its broader communications, Harvard has also acknowledged the challenges of a polarized era, noting that universities must balance free debate with social responsibility.

Journalistic responsibility requires distinguishing between verified fact and speculative claim. While it is possible that individual faculty members at Harvard, like individuals anywhere, hold controversial personal views, there is no evidence that in 2018 any panel formally convened by the university served as a platform for endorsing left-wing violence. Instead, what appears to have happened is a conflation of academic discourse with political partisanship, filtered through the lenses of mistrust and ideological conflict.

It is also worth considering the academic context in which discussions of violence occur. Scholars often rely on case studies of historical events, such as the civil rights movement, anti-colonial struggles, or labor uprisings, to draw conclusions about the conditions under which movements succeed or fail. These discussions are not endorsements of violence but attempts to understand the dynamics of social change. To accuse researchers of advocating violence simply because they study it is akin to accusing criminologists of endorsing crime or epidemiologists of supporting disease. Nevertheless, in a polarized media environment, such distinctions are easily lost.

The rumor surrounding the 2018 Harvard panel has endured partly because it feeds into a larger debate about the legitimacy of protest itself. On the American right, the violence associated with left-wing movements such as Antifa or with riots following the murder of ...